Gary Paulsen, who died last week at the age of 82, probably could have been a literary titan of a different kind, if he’d wanted to go that route. Like Robert Stone or Richard Brautigan, Paulsen was born into poverty, reared in the wartime culture of the late Depression, and eventually found his calling as a novelist writing in the vernacular of a wounded and humbled America. Unlike them, Paulsen wrote for children.

He was among the most prolific children’s authors in American history, publishing about 200 books over more than half a century (his final novel, already in production at the time of his death, will be released next year). Several of those books — Hatchet, Dogsong, The Winter Room — have achieved an iconic status among young people that few books ever do. I must have read Hatchet a hundred times as a kid — an experience which, I can now admit, hardly made me unique. Since at least the ’80s, Gary Paulsen books have been like scripture for a certain kind of child.

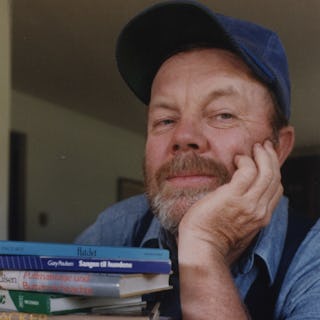

Part of the allure, admittedly, was always Paulsen himself. The ballad of his life, outlined on countless About the Author pages, was a tale as grand as any of his novels. Gary Paulsen dug up a snapping turtle egg and ate it raw, just to know the taste (true). Gary Paulsen ran the Iditarod, all 938 frigid miles of it, with his dog team (true). Gary Paulsen sailed alone to Fiji (true). Gary Paulsen got headbutted by a moose and only lost three teeth (basically true).

But mostly it was the books. They stood on their own merits. There was an uncommon honesty to them, a frankness about the darker side of living. There was irreverence, a pleasant disdain for pretension and authority. And there was respect. You couldn’t miss it, the respect Paulsen had for his readers. Each of his stories affirmed the inexhaustible ability of young people to grow and learn on their own terms, in the wilds of their own lives, far beyond where parents or other adults could reach them.

One of Paulsen’s early hits, for example, was Winterkill (1976), a novel for middle schoolers about a homeless boy in a remote Minnesota village who is manipulated and extorted by a small town cop made cruel through his own private suffering. Or consider The Car (1994), the Paulsen book most likely to piss off a parent, about an abandoned son who builds a sports car from a kit his father was too lazy to assemble, then brazenly pilots it across the country. It’s a hilarious send-up of the generic American road novel — featuring reckless driving committed by an unlicensed 14-year-old, jokes about hallucinogens, and a subplot involving war crimes and post-traumatic stress disorder — intended for readers in grades seven through nine.

Earlier this year, Paulsen published the memoir Gone to the Woods, a detailed account of his childhood and, if you ask me, his finest book. In five exquisite sections, each as tight and balanced as a novella, Paulsen narrates his own coming-of-age with a kind of clarity and rawness that is unusual even in books written for adults. Though the book is autobiographical, Paulsen’s name is uttered only twice in its 350 pages, and only by strangers: first by a Norwegian postman who collects five-year-old Gary at a remote Minnesota train depot in 1944, and then, a decade later, by a librarian who softens the delinquent teenager’s defenses by spelling his surname correctly on a library card. The author calls himself “the boy” throughout the memoir, even as events accumulate to make him “something else,” something harder and heavier, more like a man.

Gone to the Woods begins with Gary Paulsen, “the boy,” boarding a train in wartime Chicago, where he has been living with his mother and donning an Army costume to perform bar songs for soldiers on leave. On the journey from Chicago to Minnesota, five-year-old Gary comes to realize that the train his mother has put him on alone is full of wounded combat veterans from the European theatre. We witness the scene as five-year-old Gary does — the boy’s fascination with the soldiers, their moans and liquor and missing limbs, transforms gradually into an overwhelming horror. Discovered sobbing by a young GI, he confesses he has never met his father, but knows him to be an Army man. Will he find him on this train, beneath some man-shaped bundle of swaddled gauze?

War and injury are preoccupations that animate the rest of the book, and by its final section Gone to the Woods has become one of the most powerful pieces of anti-war writing by an American I think I’ve ever read. The story’s effect is enhanced by the knowledge that Paulsen wrote it for people much younger than I am, and so its moral vision is not necessarily meant to resonate with me. And yet it does.

Each of his stories affirmed the inexhaustible ability of young people to grow and learn on their own terms.

Perhaps due to how his writing life began, Paulsen never lost sight of what many adults strangely fail to remember: the world children inhabit is the same world we all do. And so for children, too, the world can be dark and senseless and sometimes intolerably cruel, but also wonderful, full of wonders, all at once.

It’s no coincidence, I think, that we meet Brian Robeson, the protagonist of Paulsen’s most beloved novel, when he is thirteen years old, the same age Paulsen was when the librarian spelled his name correctly on that library card. Hatchet begins when Brian, the only passenger in a single-engine plane soaring over the Canadian wilderness, witnesses the pilot suffer a fatal heart attack. In what is surely the most harrowing opening scene in all of children’s literature, Brian then must pilot the plane alone until it runs out of fuel, grimmly planning for the crash landing.

Deducing the plane’s controls through trial and error, Brian manages to avoid the certain death of the dense forest and plunges instead into the waters of an L-shaped lake. Marooned on the shores of that lake for almost 60 days, the thirteen-year-old survives on tenacity and will. Again through trial and error, Brian teaches himself to build a shelter, to make fire, to harvest berries, to take fish and grouse (which he calls “foolbirds”) — to survive. I read it in fourth grade, I think, and then again in fifth, in sixth, in seventh.

Going into the woods to live off the land is a trope of American boyhood so long-standing that Mark Twain pilloried it, like Cervantes did the trope of knight’s gallantry, a full century before Hatchet came out in 1986. But Paulsen’s book stands apart because it refuses to sentimentalize survival, even for a paragraph.

The novel’s turning point comes when Brian, overcome with the realization that no rescuers are coming for him, attempts to kill himself with his hatchet, the only tool he has. He emerges from that experience alive and with a steeliness that allows him to endure the impersonal violences of his environment: malnutrition, a tornado that demolishes his shelter, even an attempted drowning by a moose. And in a series of sequels that reframe the stakes of the typical adventure novel — The River (1991), Brian’s Winter (1996), Brian’s Return (1999), and Brian’s Hunt (2003) — the teenager-turned-survivor comes to realize that he doesn’t want to be rescued. His purpose is to remain in the woods.

There is much more to say about Hatchet, and about the scores of other classics Paulsen contributed to children’s reading lists during his long career. But I want to end with Paulsen the boy, not Paulsen the author, and there’s something I haven’t mentioned yet.

The wartime traumas of his childhood notwithstanding, Paulsen escaped his early life of dirt-poor itinerancy the way many men of his generation did: he joined the Army. By the final section of Gone to the Woods (“Soldier”), Gary has discovered that he can make use of violence — not only to defend himself, although that’s surely part of it, but also to bend circumstances to his will, to assert a kind of personal primacy over the world of wonder around him. And so, at seventeen, after stints as a carnival worker and ranch hand, Gary finds himself in basic training, “greeted by sergeants and cadres who are not quite human.”

“The procedure for incoming recruits,” Paulsen recalls, “was to systematically attempt to destroy every vestige of their previous civilian status and life.” He quickly learns that he and his fellow enlistees are the first generation of soldiers to use man-shaped targets. Having discovered that many infantrymen could not bring themselves to fire upon the enemy, the Army now wants its recruits to become accustomed to shooting their rifle only to see something that looks like a human being “spin and fall.”

Not yet fully emerged from “the cocoon of his youth,” Gary completes basic training and becomes a technician working on guidance systems for nuclear warheads. Under the tutelage of the United States Army, the boy learns to “kill properly with a rifle and a bayonet and a hand grenade and piano wire and a knife and a hand ax and a flameflower and a mortar and an artillery explosion and a machine gun and a recoilless rifle and a bazooka, even a shovel.” And he becomes very good at these things. In a few short years, he ascends to the rank of sergeant himself.

Suddenly a life defined by professional status and personal advancement is laid out before him like a road. It all becomes so clear: he can transcend his upbringing the American way, through the mastery of violence and the suppression of kindness and love for the world.

His moment of reckoning comes one night in the fraught interregnum between Korea and Vietnam, when Gary finds himself sitting with a group of older men, seasoned lifelong soldiers, who now fall absurdly under the boy’s command:

“And the boy, who was a sergeant but not of them, not like them, sat and watched them sitting in their underwear playing cards and drinking slowly, very professionally, out of quart jars, and the boy saw their scars.

Physical scars from wounds but more, many more scars in their spirits, scars that would never go away, as if the core of them, the center of their being, had spun and fallen so that part of them was dead and would always be dead and they could never be more than what they had been when they were first scarred. Would never grow.

And he did not want that.”

Although years would pass before Paulsen published his first book, it was this moment, I think, and not the earlier moment in the library, that transformed him from boy to author. By rejecting a life of violence in the American vein, Paulsen returned to the woods, in a sense, to survive alone on his tenacity and will. And he became different than he had been before. He fashioned himself into something timeless and wonderful and wholly unique. What a blessing for our children. What a blessing for us.

Jonah Walters recently completed a PhD in geography at Rutgers University. His essays have appeared in Full Stop, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.