If you’re someone who really likes books, especially fiction of one sort or another, chances are there’s a writer you are forever recommending to people who didn’t really ask. This is an annoying habit, and you know that, but somehow you keep convincing yourself that it’s relevant to the conversation and so there you are again, drunk in someone’s kitchen at 1 a.m., telling them why they should read this one author you love.

This is me with Nelson Algren. I don’t think I have ever missed a chance to tell someone that he wrote the single best piece of short fiction about professional boxing (“Dark Came Early In That Country,”) even though not many people seem to care who wrote the best piece of short fiction about professional boxing. He’s one of those writers where, the first time I read him, I got mad at the public school system for failing to tell me about this guy. Could they not have guessed that I might have been a more enthusiastic student if they’d turned me on to a guy who wrote fiction about pickpockets and hustlers and prostitutes and boxers?

I have since made it my mission to ensure nobody I know proceeds through life with this particular ignorance. This is especially true as we approach one of the rare holidays where book recommendations are truly helpful: Father’s Day. People love to get their dads books as gifts. Trouble is, whether your dad is a Tom Clancy guy or a Lee Child guy, dads who read books are not waiting around for an occasion marked on the calendar. This is why dads are notoriously tough to shop for. They tend to have relatively few but also very specific interests, and they pursue them alone, so that whatever your dad already knows he’d like to read, he’s probably beaten you to it by the time this holiday rolls around.

This is where Algren’s work comes in. Why? Partly because it’s somewhat obscure and really, really good, but also because much of it has a certain old-timey dudeness to it, but without losing its emotionally evocative power as literature.

This is equally effective if the dad in your life doesn’t consider himself much of a fiction reader. Working as a sports writer for the last 15 years, I frequently found myself in conversations with men who really liked sports, who every single day read the various websites devoted to covering them, but who would tell you that they’d never read much fiction and weren’t feeling terribly motivated to change that. What I learned from these conversations was that if I tried to recommend the classics — Hemingway, Steinbeck, Faulkner, etc. — it just ended up sounding to them like a school syllabus. If I tried more contemporary stuff — I’m a huge fan of Madeline Miller’s brilliant novels, Song of Achilles and Circe, which unite ancient Greek myths with the modern art of the page-turner — they seemed to think they might be better off waiting for the movie.

But with Algren I could point them toward a guy who wrote good fiction about the kinds of characters and subjects they were already interested in, and did it with speed and economy and quality prose. All of this is especially apparent in his fight fiction, a sub-genre I love. Just watch how he leaps straight in to start “Dark Came Early In That Country”:

“We’ll fight you on condition you don’t knock Reno out in the first two rounds,” DeLillo’s manager told me, “after two it’s every man for hisself.”

“Honor Word?” I asked him.

“A hundred dollars and you pay your own expenses to Chicago, Honor Word,” he told me.

“Do we take it?” I asked Beth.

“We take it,” she told me.

“I don’t have the expenses,” I told her.

Beth gave me the expenses.

Most fight fiction falls into one of two categories: The Fix, or The Down-and-Out Fighter Who Gets One Last Shot. Hemingway’s best boxing story, “Fifty Grand,” was of the first variety. Films like Rocky and, more recently, the Halle Berry MMA film Bruised, are prime examples of the second.

Algren came up with a third kind, which is to say he wrote varied stories that felt like realistic depictions of what life in the fight game is actually like for the brand of damaged and exploited dreamers who tend to occupy it.

The narrator of the above story, for instance, is a skilled but unheralded journeyman boxer who criss-crosses the country fighting for small purses and hoping for a breakthrough even as he finds his own passion for the sport slowly dissipating. One night during a long bus ride, he reflects on the need to stay hostile in the fight game. “But when you’re thirty-two and have been at this trade thirteen years you’ve pretty well used up your hostility.” He then tries to lull himself to sleep by ticking off the names of all the arenas he’s fought in: the Marigold in Chicago, the Rainbow Garden in Little Rock, the Armory A.C. in Wilkes-Barre. “Just before I fell asleep I knew those were the names of the places where I’d used up my hostility.”

This is a more eloquent and succinct version of something I’ve heard from many aging pro fighters in real life. It’s an irony of that particular business, that the time and experience you need to get good at it also results in the blunting of the tools, both physical and psychological, that you need to continue doing it. In this way, it is like life and aging in general, except that it all happens much faster.

Algren also understood the similarities that exist, then just as they do now, between pro fighters and sex workers. His story “Depend on Aunt Elly” begins with a part-time prostitute in small-town Arkansas being arrested and eventually roped into a furlough scheme which requires her to pay a devious court clerk fifty dollars a month just to stay out of prison. This forces her deeper into the business of sex work, trapping her forever in what had only been a part-time side gig, until she meets and falls in love with Baby Needles, a “Cherokee lush” and “ring clown” who whisks her away just as his boxing career starts to take off.

But when he finds out that she’s a fugitive with a hefty ongoing bill following her around, he advises her to go back to prison and finish her three-year sentence. They can start over together when she gets out, he tells her unconvincingly.

“It’ll be too late by then, Baby,” she answers him. “You ain’t got three good years left in you. ’N neither have I.”

***

Algren rose to prominence when his novel The Man With The Golden Arm won the first National Book Award in 1950. At the time, he was something of a novelty for the American literary elite. He wrote about poor people, troubled people, people who were addicts and occasional criminals, but he did it all from the perspective of a witness who was himself only a few barstools over. Algren once described being mugged on Chicago’s South Side and then getting a card from the police that would allow him to walk into the station and view lineups of that night’s arrestees in the hopes of spotting the perpetrator. He abused that card for years, he said, all so he could be a fly on the wall and hear the stories of men who’d been hauled in off the streets for one alleged offense or another.

“The only thing I’ve consciously tried to do was put myself in a position to hear the people I wanted to hear talk, talk,” he explained. This was one thing the police lineup was good for, and he used it until the card got worn out and a detective finally asked, what, he was still looking for the guy seven years later? “I said, ‘Hell yes, I lost fourteen dollars,’ so he let me go ahead.”

Algren came out of college with a degree in Journalism during the Depression and couldn’t get a newspaper job. He later served without much interest or distinction in World War II (he liked to say he began as a private and ended as one, with the procurement of wine being his primary concern during the war). His prose was sometimes compared with Hemingway’s — if you wrote relatively simple sentences and set stories in boxing rings and race tracks, that was practically inevitable — but Algren never really went in for the same brand of swaggering myth-making about his own life.

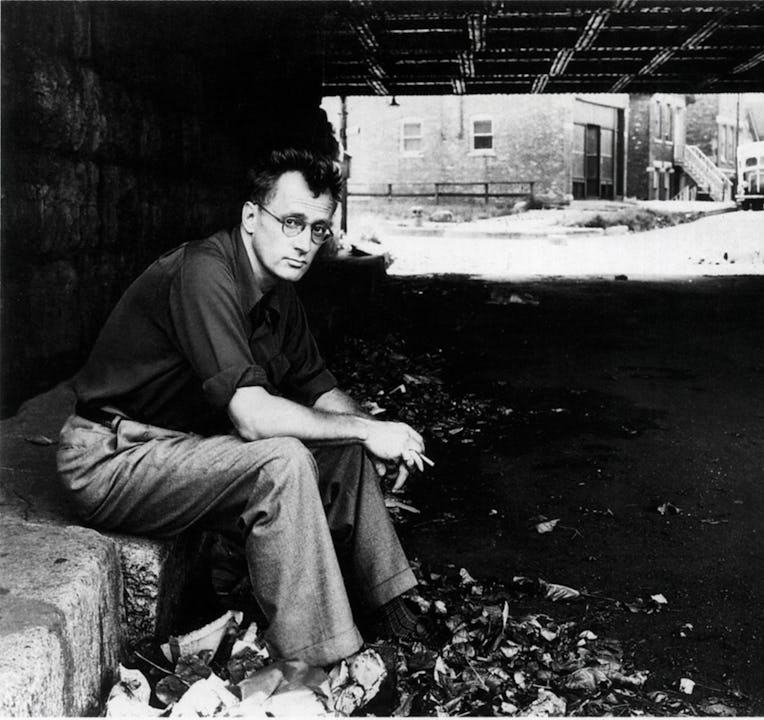

Physically, he was unimposing and unremarkable, an almost schlubby figure with glasses and tousled, thinning hair. He had a well-publicized affair with Simone de Beauvoir, though when asked about it at the time he tended to play it down, dismissing the question in one interview by simply explaining that he’d shown her around his hometown of Chicago: “I showed her the electric chair and everything.”

Politically, he was a leftist to the point of worrying his publishers at times, but he said he typically didn’t vote and wasn’t particularly committed to any organized movement. Still, it was enough that the FBI amassed a dossier on him that was said to number hundreds of pages, and which interfered with his application for a passport. After selling the film rights to The Man With The Golden Arm, he clashed almost immediately with director Otto Preminger over what he saw as Preminger’s disdain for the characters and tendency toward sensationalizing rather than empathizing with them, and he essentially disavowed all connection to the finished movie, which stars Frank Sinatra. As Algren put it later, his time as screenwriter for the film was as severely limited as his compensation for the box office success.

“I went out there for a thousand a week, and I worked Monday and I got fired Wednesday,” Algren said. “The guy who hired me was out of town Tuesday.”

To me, Algren’s best work might be his second novel, Never Come Morning. It’s a brutal and heartbreaking story about Chicago street toughs trying to find various ways to live with dignity amid crushing urban poverty, whether that means turning to boxing or strong-arm robbery or prostitution. It’s one of those books with several scenes that, decades after reading it for the first time, remain scorched into my brain in both the worst and best ways. A part of me hates Algren for putting me through those things as a reader, while another part is grateful for the empathy and humanity he managed to put into these accounts of the daily horrors people visit upon one another.

I wonder sometimes what the publishing industry of today would do with a writer like Algren, who resists easy genre categorization. His novels and stories often have crimes and drugs and booze, but they’re definitely not crime novels or Hunter S. Thompson-esque misadventures about substance abuse. There’s a certain toughness to them, sure, but there’s also too much human frailty for the hard-boiled set. Algren himself was even unsure of how he fit in. According to Kurt Vonnegut, who taught alongside him at the Iowa Writers Workshop, Algren once referred to himself as “the penny-whistle of American literature.”

That’s another reason why it works as a recommendation or a gift. It’s because even among literary types and voracious readers, a lot of people have never even heard of Algren. For whatever reason, his stuff didn’t find that permanent landing spot in the American literary canon. He’s not often taught in schools, and his name doesn’t come up alongside the mid-twentieth century literary giants (though Hemingway himself did once call Algren the second-best fiction writer in America — after Faulkner). And since so much of his work focused on characters driven to extremes by the economic meat-grinder of American capitalism, a lot of it feels very relevant still.

Maybe that’s why I can’t let it go and feel so compelled to keep shoving his books into people’s hands. This is so good, I think each time I read him. All these decades later, it is still good. The fighter must blunt his tools by putting them to work, using up his hostility, but the writer gets to channel his into something that lasts, at least occasionally. All it takes is for someone to pick it up later and give it a chance.

Ben Fowlkes covers combat sports and sometimes writes fiction. He lives with his two daughters in Missoula, Montana.