Welcome to I Was Wrong About, a series of reconsiderations and mea culpas.

Rage Against the Machine was my favorite band in middle school. The Fleetwood Mac records that most frequently circulated through my childhood household left me cold, and I needed something with more of an edge to fit my emergent gamer sensibilities. You cannot edit a Call of Duty montage together with the simmering melodrama of “Never Going Back Again,” but “Guerrilla Radio”? From an album called The Battle of Los Angeles? That fit the bill perfectly.

But while Rage’s white-hot anti-capitalist politics were never a secret, the band’s radical overtones were still lost on me, as they were on a wide swath of Americans. Our family van was often tuned to a talk show host named Michael Savage, who frequently endorsed a plan to detonate a nuclear warhead inside the Afghan cave networks where he believed Osama Bin Laden was hiding. Savage used Rage’s “Killing in the Name,” one of the most nakedly anti-police songs ever recorded, as his bumper music. I couldn’t see the irony until years later.

In fact, for much of my youth, Rage Against the Machine had no effect on my social values. I was not an overtly political child — certainly not in the revolutionary tradition — and when I was first brought into any sort of coalition, at the age of 17, it was on the back of Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign. That was the moment I formally renounced my Rage fandom; rap-metal was cratering into the absolute nadir of its cultural currency, and my taste had moved on to the Pitchfork catalog. (It’s also probably not a coincidence that I was no longer playing Call of Duty as much.)

But more importantly, the sort of serrated, insurgent anarchy advertised by the Morello-de la Rocha songwriting braintrust simply appeared out of step in a discourse environment in which pundits were genuinely bandying about an “End of Racism” after North Carolina turned blue. It’s mortifying to admit this, but I watched Rage Against the Machine’s famous protest concert against the 2000 Democratic National Convention on YouTube and thought, kind of lame. At that stage of my moral development, the band reeked of a disaffected edgelord pomp — some Heath Ledger Joker shit — when I was too busy feeling good about America. I left for college as a staunch institutionalist, bringing with me a sense of optimism and a copy of the first two LCD Soundsystem records on vinyl.

Looking back, it’s honestly shocking to consider how overtly apolitical the 2000s indie rock boom was, and how quickly those artists supplanted Rage in my rotation. Interpol primarily wrote songs about listless New York City evenings, Arcade Fire focused on the ennui of suburbia, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were either heartbroken or having a really good time at a party. There was not a shred of protest between them, even as they bloomed and died through Occupy Wall Street. In fact, I’d go as far to say that the roiling fury one must concoct to write a Rage song was a little bit uncool in those protean late Obama years.

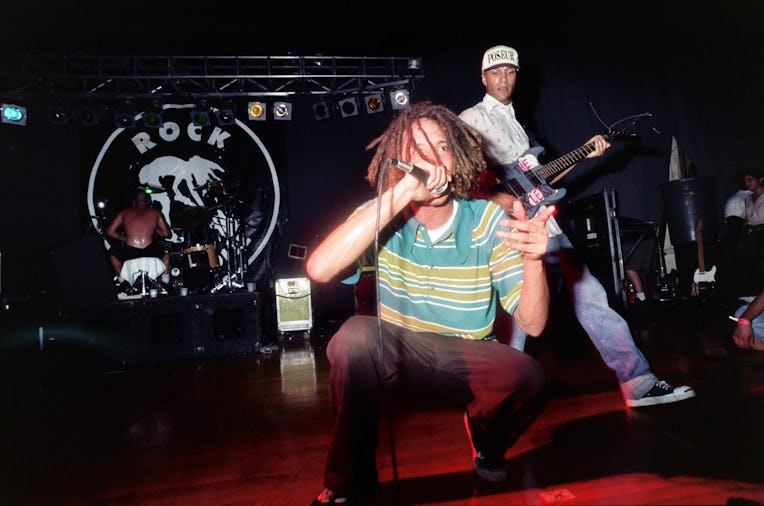

It may shock you to learn this, but I am no longer feeling good about America. The Obama coalition was sundered by the 2010 midterms, and our political procedures have felt like a long, slow, painful joke ever since. The only response any sensible person can have to, say, the Trump ascendancy, the looming climate armageddon, and a medieval Supreme Court is a cry of anguish and bloodlust, which is to say that Rage Against the Machine was right on the money all along when they sang about the generational horrors of European colonialism, or the many ways American fascism is sheathed in so-called family values. I’m not sure when this officially occurred to me, but I do recall revisiting their hits — songs I hadn’t listened to in decades — in the summer of 2017, right as police were twiddling their thumbs during the Charlottesville showdown. Zack de la Rocha, the band’s singular frontman, was never one for subtlety, which made me even more embarrassed that it had taken me this long to actually hear his words. Those that work forces really are the same that burn crosses, aren’t they?

I wasn’t the only one to unfairly dismiss a terrific band with something to say — arguably the entire music media apparatus had happily relegated Rage Against the Machine to a lowbrow tier of conspiracy theorists and disgruntled shut-ins. Pitchfork, the eternal millennial tastemaker, didn’t review a Rage album until nearly a year into Trump’s presidency, a good 26 years after the band’s formation. (Rage’s debut self-titled album was blessed with a revisionist 9.1 out of 10.)

I’m glad that Rage Against the Machine is finally getting its day now. The tide has turned aesthetically; nu-metal is in the midst of a small, semi-ironic revival, with Urban Outfitters selling Korn shirts and Slipknot members attending New York Fashion Week. De la Rocha, meanwhile, is being treated like an anti-establishment legend — akin to the way boomers treat roots-rock crooner and legacy anti-Vietnam War figurehead John Fogerty. Run the Jewels, perhaps the greatest torchbearer of the Rage’s legacy, invited de la Rocha to rap on a song about liberating a prison. He had never sounded more at home.

On our current trajectory, it seems like Rage’s message of resistance will remain relevant indefinitely. But even if the impossible happens, and late-aughts liberal bliss comes home to roost, I will never again be so docile. Rage Against the Machine was right for a really long time. No wonder they were so pissed off about it.

Luke Winkie is a writer in Brooklyn.