No one knows how Ambrose Bierce died. If you haven’t read his work, this is a salient fact about him. If you’re already a fan, you know it makes perfect sense. Ambrose Bierce, whose name I sometimes mutter to myself for the joy of how odd and pleasing it is, has, in the years following his 1913 disappearance into the Mexican desert, been credited as a foundational writer of weird fiction and horror. During his lifetime, he was more famous as a prolific muckraker. His stories happen to be very good. Sometimes, you hear writers talk about their early influences, check those influences out for yourself, and, after the requisite encounter, think, “Yeah...I guess.” But Bierce’s imagination, fueled by his incredulity at the predicament of death, makes for some of the most consistently terrifying and hilarious stories I’ve ever read. Good for Halloween, sure. But better for life, since all you have before you die is a lot of time to think about dying.

Bierce was a poet and story writer, and before that a journalist, and before that a Union soldier. His time in the army haunts all his work. While he exposed government scandals and kept up witty, cynical columns for William Randolph Hearst, he also wrote a large number of short stories set during or in the wake of the Civil War — he was preoccupied with its gruesome, destabilizing nature. So many of his characters are utterly consumed by the weight of conflict, its machinations, the way it disrupts the lives of those who live near its battlefields, the way it takes or changes lives. While writers like Stephen Crane strived for wartime realism, Bierce teased out the uncanny, absurd instances when reality seemed to break down entirely. His stories are less focused on the plausible deniability of hallucination, a narrative cop-out in cases where authors are afraid of entering into the dreaded territory of genre, and more concerned with how easy it can be to accept what was previously inexplicable when it is charging towards you. Bierce likes to keep a degree of the mundane in his work, his characters smart, worldly, but otherwise normal people. Then he steps in and makes things delightfully weird.

In the story “A Resumed Identity," a man surveying a country landscape at night is soon startled by the sight of battle formations on the horizon. Columns of soldiers march slowly from the forest and disappear again without any sound. The man, described as an elderly vagrant, thinks himself a 23-year-old lieutenant. It’s only when he stops near a crumbling fort and splashes his face in a small pool of water that he understands the truth: his life between the war and the present day has vanished; all he has left are ghosts. “He uttered a terrible cry. His arms gave way; he fell, face downward, into the pool and yielded up the life that had spanned another life.”

That last line is typical of Bierce’s supernatural fiction. For one, the narration implies the presence of a not-indifferent observer. Often, Bierce’s stories are relayed by purported future historians who are simply wading through an archive, or by narrators who have heard the tale from someone else. The first line in “A Jug of Sirup” is, “This narrative begins with the death of its hero." A little bit Rod Serling, a little bit Mark Twain. But Bierce’s style is often in service of the unknown. Nature harbors a slippery intelligence not easily discerned and also seems to provide safe haven for all manner of monsters. As such, Bierce’s characters usually find themselves in nature at night before something strange happens. “The Damned Thing” features a Predator-like creature that lurks in the trees, unable to be seen except for the impression of its feet and the objects it pushes out of the way. “An Inhabitant of Carcosa," presumed to be the inspiration for Robert W. Chambers’ The King in Yellow, which later inspired H.P. Lovecraft, shows a dead man wandering in the nature-choked ruins of his dead city.

These uninhabited settings aren’t treated as liminal spaces between life and death, or good and evil. Bierce makes plain that his characters are paying rapt attention to their surroundings and that, because of this, they are uniquely attuned to things that seem off. In “A Tough Tussle,” he writes, “He to whom the portentous conspiracy of night and solitude and silence in the heart of a great forest is not an unknown experience needs not be told what another world it all is – how even the most commonplace and familiar objects take on another character.” It’s the noticing of this other character that exposes the poor souls in Bierce’s stories, almost as if they’re asking for it, almost as if they’ve left the natural world entirely.

The supernatural “it” in question tends to be ghosts, but more often than not, Bierce’s characters are already dead, they’re just unaware of it. This recurrent feature in his fiction accrues a simultaneously unsettling, amusing, and profound effect the more you come across it. How terrifying to think you could fail to notice your own death. How hilarious to think that some people, like the deceased shopkeeper in “A Jug of Sirup” who simply continues to do his job, are so locked into the rhythm of their own lives that not even death could stop them. How nice to imagine death can be accepted so quickly.

One of the consummate pleasures of Bierce’s prose is his marriage of flowery language with evocative, chilling scenery. Part of me thinks this comes from his wartime experience, when, among other things, he was a geographical engineer and mapmaker. In “The Death of Halpin Frayser," an amateur poet from a well-to-do family tries to allay the fears of his hot mom (with whom he’s in a very Oedipal relationship), who fears she’s seen a premonition of his death in a dream. Later, he himself dreams he’s being chased through a nightmarish forest, every surface seemingly dripping in blood. The pursuing apparition only makes itself known by its laugh, “a soulless, heartless, and unjoyous laugh… a laugh which culminated in an unearthly shout close at hand, then died away by slow gradations, as if the accursed being that uttered it had withdrawn over the verge of the world whence it had come.”

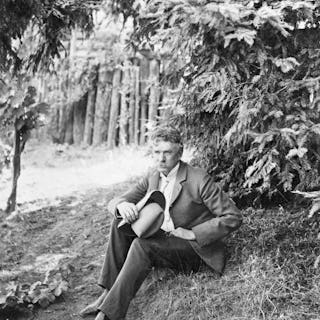

By all accounts, Bierce was a bit wild. He was wounded twice in battle, the second time from a bullet that struck his left temple (“broken like a walnut” he later described) resulting in a traumatic brain injury. That same year, in 1864, he was captured by Confederate soldiers in Alabama during a reconnaissance mission, but escaped before they could send him to prison. Following his resignation from the Army, Bierce married and had two children, but he was often away from home with work and didn’t seem all that bothered about the marriage. It’s hard to know how much he was bothered by the fact that he outlived both his children. His son, Day, shot himself and his daughter, Leigh, died from alcohol-related pneumonia. I suspect Bierce was the kind of person who, though technically on the right side of history, probably wasn’t all that enthusiastic about it. (In his famous fake resource The Devil’s Dictionary, he defines aborigines as “persons of little worth found cumbering the soil of a newly discovered country. They soon cease to cumber; they fertilize.")

What defined his life, more than a marriage or a family, was war. In October of 1913, at the ripe age of 71, he made the rounds of some old Civil War battlefields before heading to Mexico on the pretense of witnessing the Mexican Revolution. In a letter from Chihuahua, he wrote “I leave here tomorrow for an unknown destination.” No one knows what happened to him after. There are several accounts of possible Bierce deaths, perhaps in service of Pancho Villa, perhaps killed by Villa himself. Unlike his characters, Bierce didn’t see his death coming. The best we have is hearsay, which seems like the last hurrah Bierce would have enjoyed. The best endings are often inexplicable.

Nicholas Russell is a writer from Las Vegas. His work has been featured in The Believer, Defector, Reverse Shot, Vulture, The Guardian, NPR Music, and The Point, among other publications.