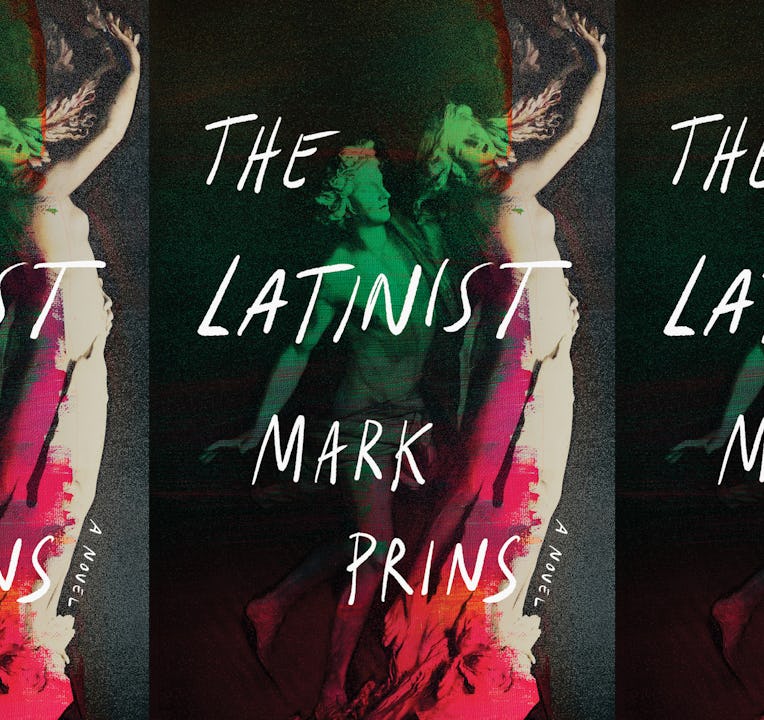

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a snob. Thrillers are one of the genres that get the short end of my taste: I had my Dan Brown phase in high school, but in the intervening years I’ve found it harder and harder to forgive the genre’s tolerance for contextual sloppiness in the service of a tight plot. But when I heard the advance reviews for Mark Prins’s The Latinist, I couldn’t help but be interested. This is, after all, very much my bailiwick: a thoroughly academic thriller built on the often delicate and vulnerable relationship between doctoral student and supervisor and, to top it off, framed as a reworking of the myth of Apollo and Daphne as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which the two protagonists know nearly by heart.

In this story as Ovid tells it, the god Apollo offends Cupid by denigrating the younger god’s skill as an archer. As revenge, Cupid strikes Apollo with an arrow that ignites fierce longing for the river nymph Daphne, and at the same time strikes Daphne with an arrow that has the opposite effect, making her flee Apollo. The god pursues, eventually catches, and attempts to rape her. She cries out to her father, the river god Peneus, and he transforms her into a laurel tree, placing her forever beyond Apollo’s reach. It’s a solid framework for a thriller; indeed, there’s an argument to be made that nearly every eroticized thriller retreads these narrative beats. In any case, if anything were going to make a convert of me, it would be this.

The academy might seem an unlikely setting for a thriller, but for anyone who knows it well, it’s nearly perfect. Old universities are bloated feudal institutions overrun by a modern management class that try desperately to hang on to their antiquarian charm. They’re ponderous vessels that change their course slowly if at all, full of people who have fond memories of the days when you met your colleagues’ wives only once a year. They are near perfect settings for a drama about the abuse of power, because the teacher-student relationship has inequality built into it and is, in some respects, immune to remedy: a teacher knows more than a student, and a teacher’s assessment of the student carries weight that a reciprocal assessment does not. That Prins chooses Oxford for his setting only underscores these features, since its genuinely medieval system of governance and reliance on personal relationships makes a supervisor’s cooperation even more essential for a student. The surroundings are idyllic; the setting is very much not.

The student in question is Tessa Templeton, an American doctoral student writing a dissertation on the ancient Roman poet Ovid while teaching and doing research on a minor poet named Marius. Her former long-term boyfriend has just left. Her supervisor, Christopher Eccles, has been extremely supportive of her career but, in the wake of his own divorce, decided to tank Tessa’s job applications with a bad recommendation letter in order to keep her at Oxford with him. Tessa discovers this early in the novel, and thus begins her rejection of him and his invasive and controlling pursuit of her.

At this point, the novel begins alternating between Tessa’s and Chris’s perspectives and displaying its structural vices. It’s not that Prins attempts a serious moral redemption of Chris — the narrative perspective doesn’t attempt to excuse his stalking — but he does want to make Chris into a compelling antagonist who becomes personally interesting even as he remains repulsive, and this is beyond Prins’s powers. Part of the trouble with The Latinist is that so much human evil is deeply boring. Chris has the checklist of traits that are supposed to make an antagonist “complicated” and therefore more sympathetic — a working-class background; a ruptured relationship with his mother; the illness and immanent death of said mother — but they fail to make his stalking psychologically interesting: he’s an entitled man who tells himself stupid and transparent lies, very nearly a stock type. It’s not impossible to make such people interesting; indeed, Iris Murdoch made a career out of it. But Iris Murdoch also believed in the literal reality of good and evil, and she sketches people doing nasty and wicked things with a satirist’s eye: there is always something absurd in their delusions, something that draws the reader’s attention to the gap between how they see the world and how it is. Often their lies are inventive; they are clever in their self-deception. Chris is not such a one, and the back-and-forth between his point of view and Tessa’s serves only to gesture at empty moral “complication” without the psychological acuity that would carry it beyond mere gesture.

Part of the trouble with The Latinist is that so much human evil is deeply boring.

When the novel isn’t attempting to sell us on a somnifacient antagonist, it executes its vision reasonably well. The Oxford college quads and corridors provide plenty of opportunity for the pair to watch one another or to speculate on being watched, both of which are key to any story of eroticized obsession. Tessa’s escape to an archaeological site in Italy gives her the ace in the hole that she can use to escape from Chris and a taste of the romantic freedom that could be hers once she does so — it’s narratively economical, and Italian cafés are nice places to imagine escaping to. All this leads up to a well-written and appropriately dramatic academic confrontation at a conference back in Oxford, where Tessa’s humiliation of Chris seems to complete her triumph. She doesn’t need his letter; she’s made her own reputation, and professionally there’s nothing more to fear.

This would serve well as the final beat in the novel’s conscious recasting of the Apollo and Daphne story. To its great detriment, the novel fails to end there, and when it finally reaches the final portion of the myth, it does so with a twist that confronts the reader in the most unpleasant possible way with the limits of the novel. It does not illuminate the myth; it does not transpose it into modernity with grace or tact. There is nothing wrong with innovation in the retelling of myth; innovation is the lifeblood of such stories. Euripides was the first to make Medea deliberately kill her children: a shocking innovation, but a highly generative one. Prins’s innovation here is neither clever nor generative; this is a fault but not a vice. His self-congratulatory epilogue, however, is inexcusable. I don’t mind a novel that telegraphs its goals and doesn’t succeed in meeting them, but it’s almost insulting to watch that same novel award itself a medal afterward.

The Latinist is plainly the result of long and painstaking work. As a classicist myself, I appreciated Prins’s careful attention to detail, even to the point of composing his own Latin poetry. Writing verse in a long-dead language is no easy feat; writing it successfully in an obscure and difficult meter is worth genuine kudos. Prins also knows what kinds of things can go wrong in academic life and just how vulnerable a junior scholar is, especially when she’s a woman with a male dissertation supervisor. The elements of a good thriller are almost all present, but they are handled poorly at crucial moments, and the novel’s feminist slant is undermined by the descriptions of Tessa’s own erotic imagination. On the very first page she imagines Chris smoking, with “the red nub between Chris’s fingers, the tip crackling as he stole one last illicit drag before ejecting it through his casement window,” which reads like a parody of a man writing a woman’s fantasy.

Late in the novel, Chris accuses Tessa of making her own compromising choices, and Tessa takes the accusation to heart. The scene sums up the story’s treatment of its own mythic blueprint: what if Daphne had done bad things too, and what if she got to do them to Apollo? As a twist on Ovid, whose poetry has sustained countless reworkings, this is pretty thin gruel. When we read about the god chasing the nymph, we see an old version of a story still older than that: a powerful figure dominates a powerless one with the threat of force. It’s easy to imagine the power changing hands and to see a different person doing violence instead. But this fails to take the myth seriously. Daphne runs from someone whom she can never overcome by force, and we continue to tell this story because we know that answering power on its own terms is so often impossible; even Daphne’s father, to whom she cried out, couldn’t do that. But we can be transformed, and thus the terms on which we face power can change. Maybe we ought to imagine those possibilities instead.

Daniel Walden is a writer and classicist. He spends his time thinking about Homeric philology, Catholic socialism, musical theater, and the Michigan Wolverines.