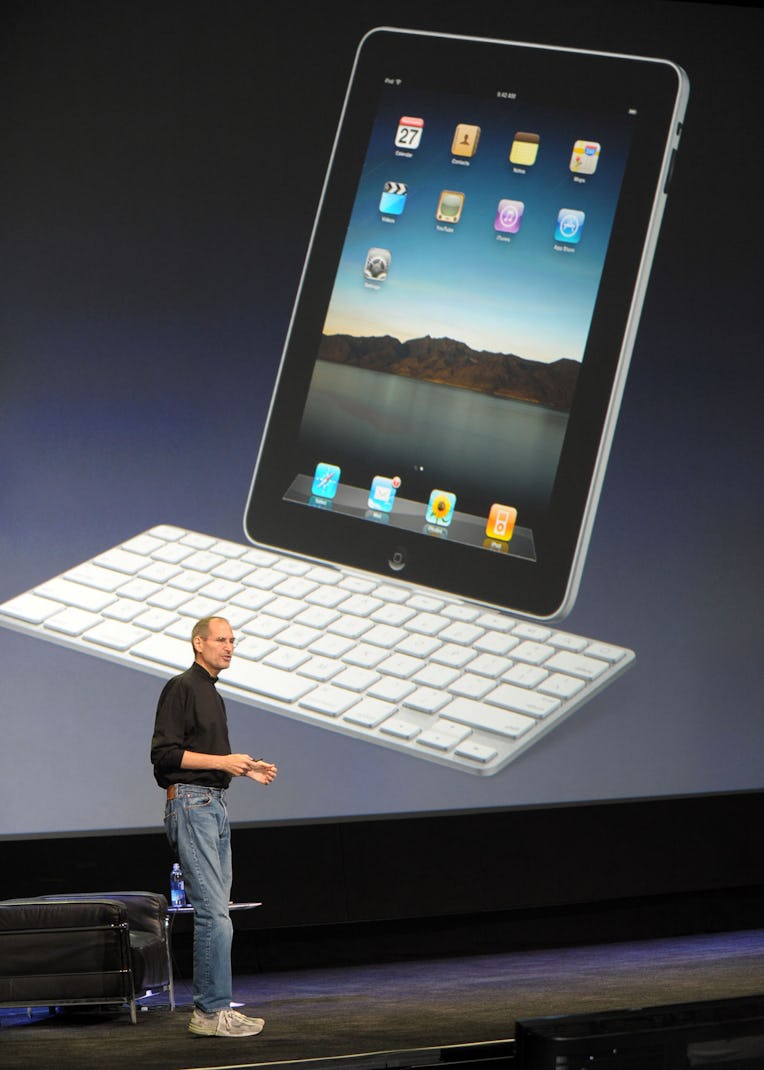

There is a popular portrait of Steve Jobs, still young, sitting at his desk in a pair of light-washed jeans and beat-up gray New Balances. The screen of Jobs’s Macintosh Classic II, the plastic-laden personal computer Apple debuted in 1991, glows softly in the background. To this day, the image surfaces from time to time, in mood boards and style paeans.

The Jobs image has become a beacon for brands searching for a new definition of luxury — one that is more honest but no less self-assured, a rebuke to the baroque maximalism of Gucci or exasperatingly dour nihilism of Balenciaga. This muted luxury lives in the overlap between the early, apocryphal days of Apple and the concrete grayness of New Balance — and now that aesthetic has been resuscitated to sell upmarket streetwear.

It would be unfair to diagnose the enduring nostalgia of Mac aesthetics uniformly — broadly speaking, women don’t wait in line outside the Aimé Leon Dore store. It seems to afflict mostly men, a fashion demographic that adopts imperceptible tweaks in pant hems and sends out press releases for their audacity. So it makes sense then that the victor of the ugly-shoe wars should be Mac in spirit: New Balance, a brand so determined to avoid gimmickry that it effectively fixed the look of its product 50 years ago, but is now the elevated streetwear canvas of choice, a sort of benign corniness that’s so boring it must signal something quietly fascinating (it doesn’t). The 990, a shoe so nondescript it barely even exists, is worn like a secret handshake among aficionados and creative types, its orthopedic sobriety and mouse gray dullness winking at its wearer’s sagacity.

Apple and New Balance both signify a nonchalance, the belief that simplicity means you aren’t trying.

The symbiotic relationship between Apple and New Balance is easy enough to trace. Jobs favored, seemingly exclusively, gray New Balance 990s, part of his personal style that eventually calcified into pastiche, a standard of head-down humility. Apple, and Jobs in particular, is the ur-Silicon Valley myth, and because we know how his story ends (in near-total market domination and godhead reverence) his and the company’s early years exist like a superficial capitalist blueprint. In January last year, Notre, the Chicago retailer, posted an image of New Balance’s recently released 57/40, a squidgy-soled number with primary color layers and an oversized ‘N’ crowding out the midfoot, as if it were experiencing a growth spurt, arranged against a Mac Classic II. The colorways of the sneaker only vaguely hearken to Apple’s early rainbow logo, but the link between the brands is such that the association feels natural. Aimé Leon Dore has exploited the aesthetic to an even more ingenious degree to promote its recurring partnership with New Balance, offering slightly tweaked resurrections of the latter’s styles of the 1990s. In one ad, ALD excavates a character from a decades-old New Balance campaign: an alte kaker with a stogie dangling from his mouth and the New York Times tucked under his arm, wearing box-fresh NBs.

Apple and New Balance both signify a nonchalance, the belief that simplicity means you aren’t trying, “not trying” being a persistent, undying measure of personal style. This all used to be subtext. In an ad for the artist Tom Sachs's latest sneaker (with Nike, but the argument holds because it's pitched at the same collab-addled demographic), the subtext becomes text, specifically an overlong text admonishing that your sneakers should in fact be boring, as opposed to the most interesting thing about you, a funny little bit of negging that skips over the fact that wearing sneakers which you've either entered an online lottery to buy or almost certainly purchased at a hysterical resale markup does not exactly point to a fascinating personality. One of the more insidery New Balance collaborations in recent memory was with Justin Saunders, the designer who works as JJJJound and whose unadorned serif logo and unflashy men’s basics serve as an aesthetic wayfinding station for the visually overwhelmed. It’s probably not insignificant that Saunders began JJJJound as an online moodboard, and still refers to it that wofay, a textless and contextless stream immaculate vibe that, like a zen koan, seems to say something profound about something important, or not. Saunders’s New Balance 992 was a demonstration of true soft power: he basically did nothing to it.

The colorways of the sneaker only vaguely hearken to Apple’s early rainbow logo, but the link between the brands is such that the association feels natural.

This impulse extends beyond sneakers. The strain of late ’80s and early ’90s print advertising favored by Apple (isolated image on an unadorned background with a tranche of serif text, usually in condensed Garamond) is incredible to look at now for its sheer static simplicity, but also for the time it demands. In 2022, sitting with a print ad longer than most Instagram captions is a startling visual anomaly. And yet it’s found new purchase among a raft of brands that exhume it in a bout of post-ironic signaling. Poolsuite, ostensibly a lifestyle brand but who knows, has since last year has been marketing a line of sunscreen with overdetermined, text-heavy ads that allude to yuppie touchstones like shrimp cocktail and Diners Club, along with a website styled like an early Macintosh desktop of faux-crude bitmap graphics.

All of it is a little grating, if mostly innocuous, until its sunny disposition inevitably darkened into an NFT initiative, murkily offering “executive member” access with greed-is-good flavored ads that winks at the absurdity of the id-thrust ’80s but also pines for it a bit too much. You get the sense these are people who would almost certainly trade in the scant social advancements of the last two decades for a cocaine-soaked office party, or who like to imagine they would. This aesthetic is aped in the marketing for sex toys, alcoholic seltzers, and direct-to-consumer artisanal beverages. All of it is depressingly vacant.

It also models itself on Apple, which has managed to achieve what few other brands have, transcending its market position or even what it actually makes into pure lifestyle, a total vision of aspirational modernity. Its products are coveted, but also mostly beside the point — what Apple sells is itself. The brand has become so inextricable from our conception of modern life that it rarely presents a radical vision of the future anymore, or even needs to, instead offering granular improvements to fill out superfluous product releases, or wading into the shoals of mediocre streaming entertainment. Yet its early radicality remains suspended in our visual orbit. The serif “Think Different” ads of the late ’90s, with their black-and-white images of Einstein, Gandhi, Picasso, and other people who never used a computer, became so tethered to the idea of the brand that 20 years after they stopped appearing, the association, more lofty than demonstrable, that Apple users are possessed of an iconoclastic mind remains.

The aesthetic can be depressingly vacant.

The idea that late ’80s and early ’90s technology and their graphics now function as a visual palate cleanser is strange, but also not: The appeal surely lives there, in the innocence and promise of the still-nascent computer age, but also a reaction to the unrelenting cascade of information that overwhelms any room for a spare thought. Lodging your brand in that moment opens a trap door, an escape from the endless scroll. The imagery longs for a time when we weren’t bleary-eyed, screen-addled prisoners of our own making, idling instead inside the one when computers needed to be tethered to the wall and logging on was an act of willful determination, as opposed to a cynical compulsion. The smartphone reflex is already muscle memory, but nostalgia conjures another one, fainter but still there, when merely leaving the house meant you could be left alone.

These choices are tinged with a certain sadness. The promise of the computer age was a better, more expansive and equitable future, one which in any number of ways we’ve yet to realize. That we’re returning to those same promises can be read as a hopeful invocation of that future, or something dimmer: that we’re only able to imagine it by reaching backward, channeling a model of success whose contours are pre-traced. This aesthetic speaks to the person who sees themselves always on the verge of recognition, preemptively nostalgic for the moment immediately before their breakthrough, wearing their boring sneakers, crafting their origin story in real time, even as it’s mostly borrowed, cobbled together from bits of consumer products, always just beyond reach.

Max Lakin is a writer in New York.