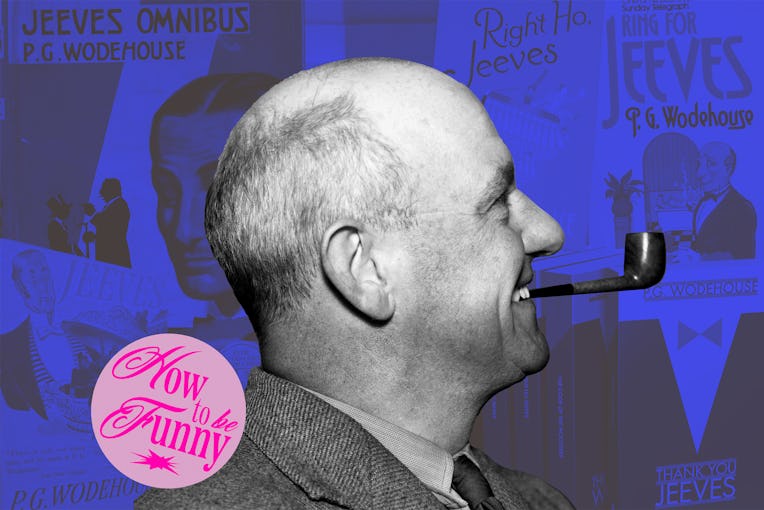

Welcome to Gawker’s How to Be Funny week, a celebration of people and things who are making us laugh and teaching us how to laugh more.

***

The consumer-existential newsletter “Blackbird Spyplane” declared Wodehouse Summer on July 26 of this year, but by that time my summer was all planned out: Mating, Say Nothing, The Glucose Revolution, Something to Do With Paying Attention, my friend’s first draft of a crime thriller. The Glucose Revolution was as good as it sounds, but the others were deftly written, and I enjoyed reading all of them, even if my opportunity cost nagged at me. Wodehouse Summer! I was missing it. It was like learning the theme of prom was Nervous Dorks after I had already ordered my pizza and rented Showgirls.

Anyway, the snail was off the thorn and the leaves were looking crisp around the edges by the time I cracked three of the best: Right Ho, Jeeves; The Code of the Woosters; and Joy in the Morning, published in that order by Pelham Granville “P.G.” Wodehouse between 1934 and 1946. These three novels in the Jeeves and Wooster series — about a wealthy idiot who lives in London with his famously intelligent butler — are Wodehouse’s Thriller/Bad/Dangerous, his Revolver/Sgt. Pepper/White Album, his Ride the Lighting/Master of Puppets/…And Justice For All. They are three good things he did all in a row — except he didn’t do them quite in a row, since during that period he also published six other novels and at least two plays.

The image of Wodehouse as some sort of manic literary beaver is one of the singular pleasures of reading his work. His professional career began in 1902 with the publication of his first novel and ended with the release of his 70th in 1974, less than a year before he died. The man fit in 25 years of full-time work before the first talkie hit theaters, back when the dominant media for comedy were stage shows and print. In the 21st century, prose humor is a kind of charity division whose entrants fall into two categories: gift books by people who have been funny on television and novels that say “uproariously funny” on the jacket even though they are not funny at all. Actually funny books by people who identify as writers are no longer profitable, but when Wodehouse was in his prime, you could make a living at it.

The thing about making a living as a writer is that it’s not how much you publish; it’s how much you publish divided by time. The modern writer solves this problem by inheriting generational wealth, but the finances of the Wodehouse family collapsed in the years leading up to his eighteenth birthday, and he got a job in a bank instead of going to university. I mention this biographical detail because Wodehouse writes like a man who has worked for a living, i.e. with attention to craft and evident determination never to go back. I believe this second motive accounts for the volume of his production.

Serial readers of Jeeves and Wooster novels will find them marked by certain similarities at the level of plot: conflicts, devices, and even scenes recur throughout the series. The major crisis in Joy in the Morning, for example, erupts when Bertram Wooster accidentally gets engaged to the author and intellectual Florence Craye — a problem that strongly resembles his involuntary engagement to an amateur poet in Right Ho, Jeeves, and his bid to escape the same woman in The Code of the Woosters. At least three of the novels also begin with Jeeves rejecting some new affectation Bertie has taken up: a banjolele in Thank You, Jeeves; an alpine hat in Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves; in Right Ho, Jeeves a white mess jacket that Bertie acquired in France.

Like the banjolele and the hat, the mess jacket leads to a kind of cold war between Jeeves and Bertram, who decides that his butler has gotten too high-handed and the time has come to assert his authority as an employer. Jeeves complies, much as he did in banjo and hat. Midway through Right Ho, Jeeves, however, Bertram finds himself desperate for Jeeves’s help, and he is haunted by the feeling that it is all happening again:

“In the past,” Bertie says, “when you have contrived to extricate self or some pal from some little difficulty, you have frequently shown a disposition to take advantage of my gratitude to gain some private end. Those purple socks, for instance. Also the plus fours and the Old Etonian spats. Choosing your moment with subtle cunning, you came to me when I was weakened by relief and got me to get rid of them. And what I am saying now is that if you are successful on the present occasion there must be no rot of that description about that mess jacket of mine."

Would it shock you to learn that Jeeves does succeed in saving Bertram, and that he does exact his price in the disposal of the white mess jacket? It could not end another way. But en route we get the joke above, in which Wodehouse steps out from behind the curtain, acknowledges the reader with a kind of bashful grin, and admits he’s been recycling his plots.

Wodehouse doesn’t just recycle comedic devices, though; he also recycles his joke about recycling them. Two novels later, in Joy In the Morning, Jeeves suggests that Bertram replace his aunt’s lost brooch with a lookalike from a London jeweler, and Bertie notes that “the mechanism is much the same as that which you employed in the case of Aunt Agatha’s dog McIntosh.” Here Bertie refers to Wodehouse’s “Episode of the Dog McIntosh,” a short story published seven years earlier in The Strand Magazine in Britain and in Cosmopolitan in the US. A version of this joke, in which Bertie or Jeeves observes that what’s happening to them now is eerily similar to something that happened in the past, recurs in almost every novel.

I love it when Wodehouse does the didn’t-this-happen-before gag. It provides me with a moment of what turtleneck owners call verfremdungseffekt: the “distancing effect” that occurs when you are reminded that you are not reading a report of actual events but rather the product of some weirdo’s imagination. Every time Wodehouse does this joke, it shifts the plane of the book from the life of Bertie and Jeeves to the life of the author himself. I imagine him halfway through his next novel, which he must submit to a certain publisher by a certain date so he can buy heating oil or whatever, when he realizes that he’s written the same plot before. So he winks and finishes the job.

When I was younger, I would have derided this approach as hackwork. Today I admire it as hackwork. The similarities among Jeeves novels emphasize how well Wodehouse knew how to write a comic plot, a form that, like the villanelle, is notoriously difficult and short on positive examples. It is much easier to be funny at the level of words than at the level of events. The dominance, in comic prose, of the picaresque — in which a flawed hero journeys through a series of mostly disconnected episodes, e.g. The Dog of the South, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Don Quixote — testifies to the difficulty of writing a funny plot. The all-timers are disproportionately stage plays, such as Cyrano de Bergerac or the Awesom-O episode of South Park.

To Wodehouse the novelist/dramatist, however, the principles of a funny plot are well known: a dumb guy thinks he’s the smart guy; he winds up making things worse; he gets treed by a dog or a cop or an uncle; the smart guy gets his gentle revenge. Can we blame Wodehouse if, over the course of 11 novels, he could only think of three or four variations on those beats? When he admits that he is cribbing from an earlier book, we see him working harder to make us laugh than even he is qualified to do. It reminds us of another great aspect of these novels: the author is relentlessly, doggedly at our service.

Also he needed the money. That’s the worst reason to write something, I thought, back when I was a 19 year-old English major who worked at the frozen yogurt place. Now that I write things for money, and they either please someone else or come back with a kindly worded email that makes me want to fire up the oven and crawl on in, I take a more generous view of literature’s hacks, its penny-a-liners, its one-trick ponies. I should have such a trick. The artist devotes his life to writing in order to become immortal; the craftsman devotes his day to writing in order to pay the rent. The second way makes you tired, but it also makes you funny.

Dan Brooks is a writer in Missoula, Montana.