I’m a cold weather guy. My mind doesn’t really work in the summer. I like nothing more than to take a long walk wearing three or four layers, to step into a bar and peel off just a whole bunch of coats. I’ve been known to savor words like “crisp” and “frosty,” and nothing excites me more than when the weather app on my phone predicts a sunny day in the 50s. I chose to visit Siberia in February. It’s not my most charming quality.

Much of this is bound up in my childhood in a small town in upstate New York. There are many photos of me in large windbreakers, holding apples and standing in piles of leaves. It’s romantic, sure, but I’m a bit of a sap. The return of cold weather every Fall is a comfort, perhaps even a reward for getting through New York City’s deeply unpleasant summers, when temperatures on the shadeless streets reach into the low hundreds and everything smells like garbage.

Yet every year that return is postponed a little more. The summers have become hotter and last longer. This September, temperatures reached into the mid-80s late in the month. This past October was the sixth warmest on record. New York City is now in a subtropical climate zone. It’s not hard to imagine that soon the sun will regularly be setting at 4:30 and I will be wearing a t-shirt.

Lately, I’ve been coping by watching cold weather movies. And king of them all is 1993’s The Fugitive. A remake of an ABC television show from the 1960s, it was a massive hit, making almost $400 million and receiving seven Academy Award nominations. If you haven’t watched it by now I’m not sure how that happened but I have no qualms about spoiling a movie released during the first Clinton administration.

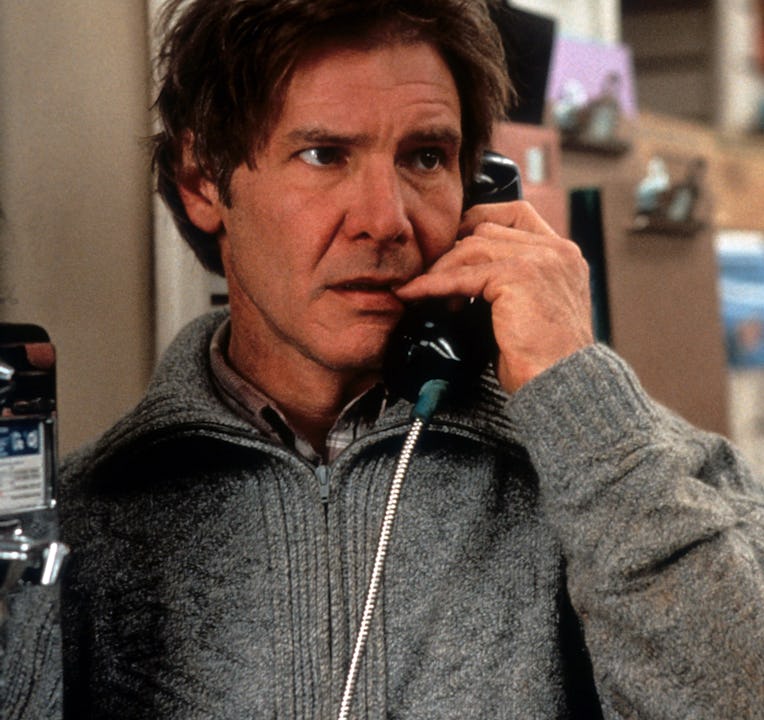

Harrison Ford stars as Doctor Richard Kimble, a Chicago surgeon and escaped prisoner who didn’t kill his wife, and he’s being pursued by Tommy Lee Jones, a Federal Marshal who doesn’t care about this fact. After surviving a prison break that turns into a bus crash that turns into a train crash, Ford finds himself on the run from the Chicago PD, Jones and his crew (including Joe Pantoliano as “U.S. Marshal Cosmo Renfro”), and, eventually, the convoluted set of conspirators who did kill his wife. Eventually, Ford returns to Chicago and reinvestigates the crime, to clear his own name and bring his wife’s killers to justice.

Director Andrew Davis made his name directing movies where martial artists like Steven Seagal and Chuck Norris battle mercenaries aboard decommissioned battleships and team up with crime fighting robots, and he brings a relentless forward movement to the material. The Fugitive functions as a series of escape contraptions, in which Ford finds himself pinned between his various pursuers and must escape by his wits and the fact that, as one character tells Jones, he’s just too smart to lose. We watch him get into and out of jams for two hours, and my excitement never flags. It’s a testament to all this tension and release that the movie works from beginning to end despite devoting significant run-time to a frankly incoherent murder-conspiracy plot.

But then this is a movie that ends with a knock-down drag-out fistfight between two deeply middle-aged men in the middle of a pharmaceutical conference, so it may all be a bit beside the point.

What’s more remarkable is that this cold, wintry movie about a wrongly convicted man on the run is among the coziest ever made. To steal the term from a favorite podcast, the cozy movie provides the viewer with often-tangential comforts — the fashion, the production design, the hairstyles — often at odds with the actual subject of the film. Think Bullitt, The Pelican Brief, Jaws 2; something tells me House of Gucci will soon be joining them. The Fugitive doesn’t skimp on such comforts. Joe Pantoliano wears a geo-patterned fleece jacket. The blue jeans are very blue. The score contains both slap and fretless bass. I want to pull it on like an old cardigan.

The Fugitive was shot during a midwestern winter, frequently at night, sometimes in frigid water, and everyone looks like they’re freezing all the time. The actors are always hunching their shoulders, their hands in their pockets, breath misting. At any point Joe Pantoliano might be wearing somewhere between 5 and 7 layers. Tommy Lee Jones is introduced telling someone to wear a coat on top of their coat, and for the next twenty minutes does nothing else but bark orders and rip open little Velcro pouches. For this he justly received an Oscar.

Like another acclaimed mega-hit of the early 1990s, The Silence of the Lambs, this movie is genuinely interested in small towns and side roads, backyards and basement apartments. We get long sequences set in an obstetrics lab and an overwhelmed emergency room. Whenever I think of this movie I’m thinking as much of the flurries and bare leafless trees as much as the one-armed man and the murder mystery. The roads are full of sleet and slush and the sky full of that soft gray light you get during a snowstorm. Arguably its most exciting sequence involves Ford melting into the crowd at the Chicago St. Patrick’s Day parade, and the camera lingers over the floats and the faces of regular, bemused Chicagoans.

In some ways The Fugitive feels like the prime example of a ’90s drama, the golden age of action movies starring men well past their twenties. In the decade between Temple of Doom and Clear and Present Danger Ford starred in eight massive hits, several of which grossed over $200 million. Forty-four million Americans paid to watch a movie about a man running up and down Chicago staircases. Both of its stars are pushing fifty, and the camera lingers long on their craggy faces, and the primary emotions we see are not ecstasy and empowerment, but fear, regret, confusion.

On top of that, real money was spent on the production. The cast is extensive, the bench deep with character actors. All those night shoots can’t have come cheap. They roll a bus down an embankment, crash a freight train into that bus, and then derail that freight train, the sort of massively destructive spectacle that today you really only get in movies starring Tom Cruise. Even all that ubiquitous snow would now be digitally rendered, one of those effects that always looks awful no matter how many times it’s applied.

It’s become de rigeur to call this the kind of movie they just don’t make anymore. Movies for adults, starring movie stars, set in real places and filmed in the real world, routinely tank; childlike power fantasies set in conference rooms and filmed in tax credited warehouses dominate our cultural consciousness. The Fugitive was released a little under two years after my birth, and yet, like my crisp, chilly childhood, feels like it arrived at the end of something. There’s a comfort in that, I guess; at least I got through the door.

To which you might rightly say: I don’t care. But this didn’t stop Harrison, and it sure won’t stop me. He leapt off of a dam and swam off in search of a one-armed man. And I? Why, I put a sweater on top of a sweater, and I rewatch The Fugitive.

Robert Rubsam writes fiction and criticism.